The gist was essentially this:

We would take a field trip to three of our town's 100+ cemeteries. Students would find 19th century gravestones that interested them, then each class would choose one person whose grave they had seen to study. I would then spend the next several months collecting as much primary source data about these people from census and probate records, town reports and military pensions. I would present what I had found to the students, and they would do research on aspects of each person's life.

For instance, they investigated the death of a railroad brakeman who had been run over by a train or what life was like for a Civil War veteran who had died of tuberculosis. The idea was that when we were done, we'd have compiled a reasonably comprehensive biography of an otherwise obscure historical figure.

Over the years however, the project has fallen by the wayside, primarily because of the huge amount of legwork involved on my part.

We did take a field trip to three local cemeteries, but students were restricted to looking at the graves of Civil War veterans.

Ultimately, almost all the students were drawn to this grave.

Clearly, it belongs to a Civil War vet, but it has fallen on hard times and is almost illegible.

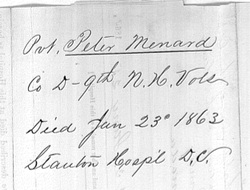

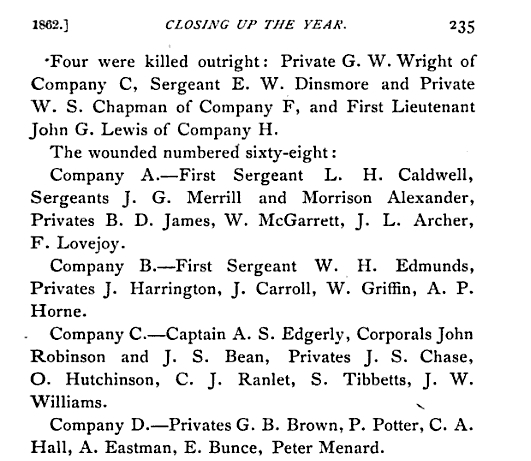

We could tell that his last name was Menard, that he had died in January of 1863 and that he had served with Company D of the 9th New Hampshire Volunteers.

After consulting with the 9th NH's Regimental History, we learned that his name was Peter Menard, aged 20, who joined the unit in August of 1892. We used that information to send send away to the National Archives for his military record.

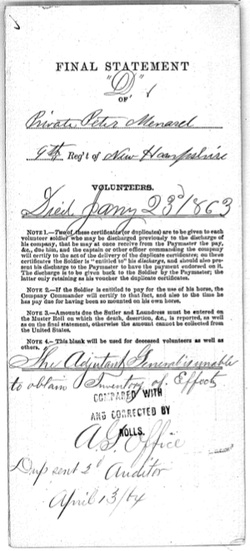

We discovered that Peter was a private and that he died January 23rd, 1863...

In Stanton Hospital in Washington, DC...

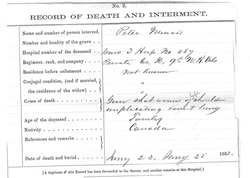

... in Ward 3, Hospital # 487 and that he died from a gunshot wound in the left shoulder (implicating bone and lung).

He was twenty years old and was born in Canada.

"The body of Peter Menard was delivered to friends(?) of his then(?) carried for burial to New Hampshire on Jan. 25th."

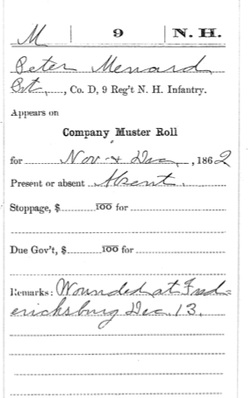

It turns out that he was wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13th, 1892.

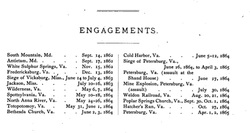

A little research turned up the battles that the 9th NH fought during the War.

Peter Menard, a very young Canadian immigrant, signed up to serve in the Union Army in Concord, NH in August of 1862. His unit saw a LOT of action, very quickly, fighting in the Battles of South Mountain, Antietam and White Sulpher Springs, before the Battle of Fredericksburg in December.

After watching Ken Burns' documentary, The Civil War (well, the section on the Battle of Fredericksburg, anyway), we learned what a debacle Fredericksburg was for the Union Army. The first day - the day when Peter Menard was shot - was a particular blood-bath. Commanding General Ambrose Burnside sent his forces charging up a hill against entrenched forces fourteen times.

The fact that Menard died in a military hospital in Washington, a month later indicates that he probably died of infection.

When we looked up the Battle of Fredericksburg in the official Regimental History, we found this:

[Addendum:

I wanted to get the basics of this project up on the blog, while everything was still fresh in my mind and while I still remembered where all the photos were. I didn't speak much to how well this worked and what - if anything - my students got out of it.

The answer is, this was a satisfying project in regards to both those criteria.

In the past, when I did this project, I spent WEEKS of my own time, researching three or four local citizens (one for each class). The students spent two or three weeks of their own time doing (or pretending to do) research. I was very worried that I hadn't put in that kind of time this year. Also, I am running desperately short of class time, as the end of the year looms larger and closer. Ultimately, I decided to focus on just one local "Dead Guy" and go over the primary source material together as a class.

I was taken aback at how engaged my students were by this. They asked good questions and put forward very solid hypotheses about inconsistencies in the dates on the documents. They got a real taste of historical research. They were especially impressed with finding our guy's name in the list of the wounded in the regimental history (see above).

In terms of what my students got out of this, these are the NH State Social Studies Standards met by this project:

- Students will use economic and geographic data, historical sources, as well as other appropriate sources.

- Draw on the diversity of social studies-related sources, such as auditory and visual sources, such as documents, charts, pictures, architectural, works and music.

- Distinguish between primary and secondary sources.

- Detect cause and effect relationships.

- Distinguish between facts, interpretations and opinions.

- Recognize and understand relevant social studies terms.

- Place in proper sequence

- Draw inferences from factual material

- Recognize that more than one reasoned interpretation of factual material is valid.

- Compare and contrast credibility of differing accounts of the same event.

- Form opinion based on critical examination of relevant information.

- State hypothesis for further study.

- Take into account when interpreting events or behaviors context of their time and place.

- Justify interpretation by citing evidence.

- Analyze environmental, economic and technological developments and their impact on society.

- Analyze the demographic impact of diseases and their treatment.

Again, I think this was worth our time.]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed