This is the second year that I've had my 7th graders make Medieval-style illuminated manuscripts from their favorite song lyrics. Lessons learned: - Give students an explicit, step-by-step checklist of what is expected.

- Give them plenty of time to complete the manuscript (the better part of a week), but only a couple of class periods. (Last year, this went on FOR EVER!)

- Keep making comparisons and connections to Medieval illuminated manuscripts. It is easy for 12 year-olds to forget why they are doing this project.

- Use Google Voice to have students explain the symbols they have chosen. This reinforces the lesson that Medieval monks enhanced their text with the equivalent of pop-culture iconography. Several manuscripts, which didn't seem all that well-thought-out at first glance turned out to be surprisingly sophisticated, once the symbolism was explained.

For several years, my 8th grade American History students used to devote a month or so to a project we called the Adopt a Dead Person Project, or as my students called it, "The Dead Guy Thing". The gist was essentially this: We would take a field trip to three of our town's 100+ cemeteries. Students would find 19th century gravestones that interested them, then each class would choose one person whose grave they had seen to study. I would then spend the next several months collecting as much primary source data about these people from census and probate records, town reports and military pensions. I would present what I had found to the students, and they would do research on aspects of each person's life. For instance, they investigated the death of a railroad brakeman who had been run over by a train or what life was like for a Civil War veteran who had died of tuberculosis. The idea was that when we were done, we'd have compiled a reasonably comprehensive biography of an otherwise obscure historical figure. Over the years however, the project has fallen by the wayside, primarily because of the huge amount of legwork involved on my part.

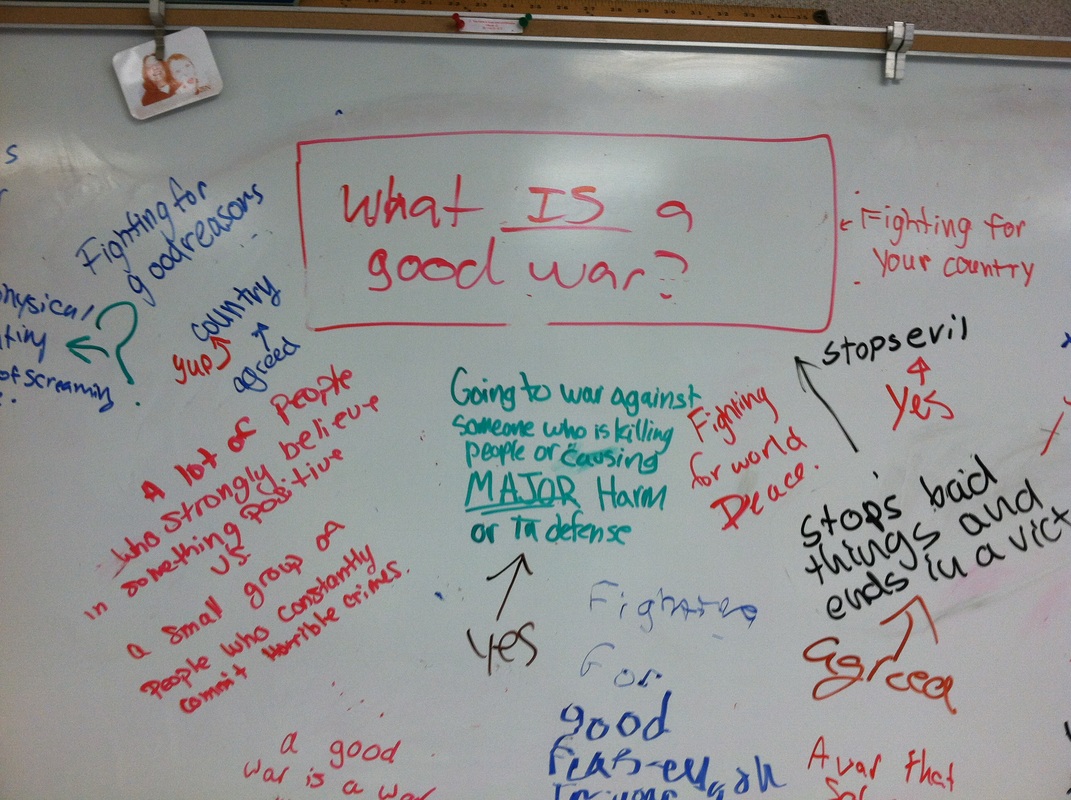

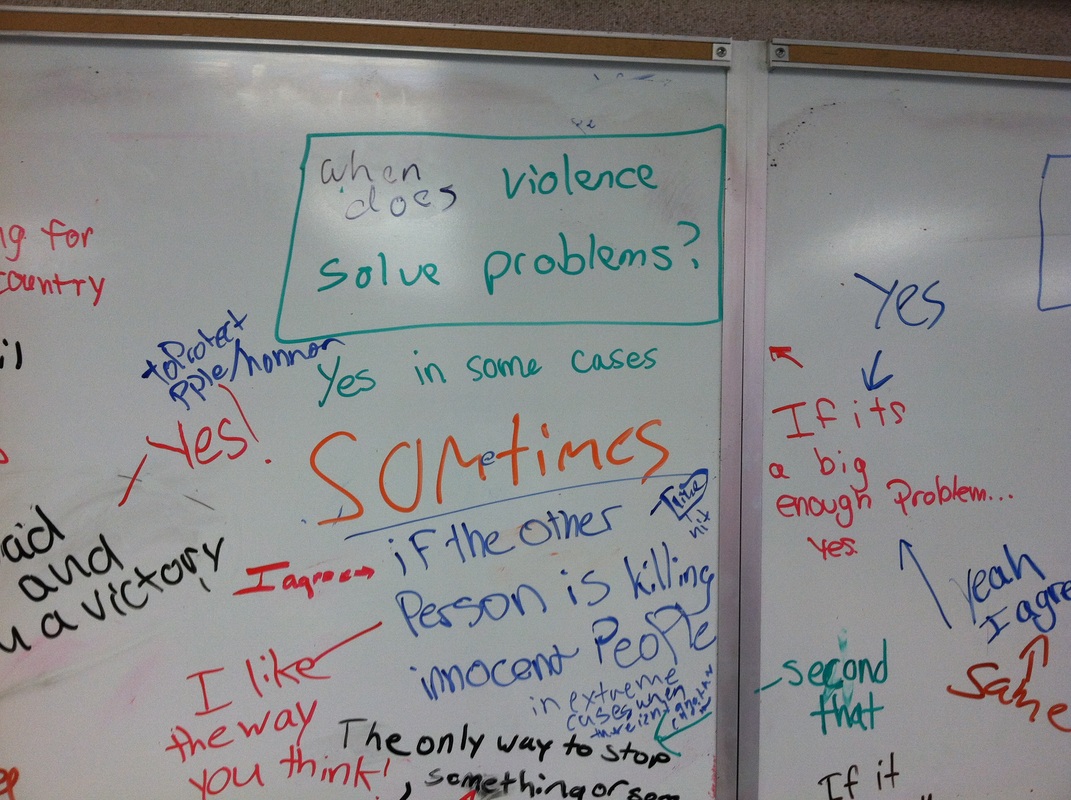

Once or twice a year, I have my 8th graders do a Chalk Talk. The goal is to have them think about and discuss knotty philosophical issues from a fresh perspective. As we start our Civil War unit, I like to ask three provocative questions: - Is there such a thing as a good war?

- Does violence ever solve anything?

- What would you be willing to kill somebody for?

This year, my students were very resistant to digging deeply into any of these questions. Q: Is there such a thing as a good war? A: "Yes." "Yes." "I don't know." "Maybe" "Probably" I discovered quickly, that for this group, I needed to frame my questions much more specifically: - What is a good war?

- When does violence solve problems?

- What would you would be willing to kill somebody else for?

A good lesson for me. As always, their answers were really interesting, if you compare them to what a Civil War-Era Southerner might have said.

Although the State of New Hampshire does not require any specific knowledge of basic, what-goes-where mapping skills from my 7th and 8th graders, I devote one day a week to it, because I can't, in good conscience send my guys off to high school, not knowing where France is. On a given day, one week, the class and I will go over a part of the world, filling out blank maps together, then one week later, the students will take a quiz on that particular part of the world.

Generally, these quizzes will take the form of blank maps, with regions, countries, etc... labeled with numbers. I have students number blank paper with those numbers, then identify the items from the map.

[Yes, this is very basic, rote learning, but I feel that there is a place for rote learning in a well-rounded education. Sometimes, students need to have a basic body of knowledge to build on for more sophisticated concepts. The steps of a bill becoming a law, for instance. Or their times-tables.]

Anyway, every once in a while, I give a slightly different type of quiz to my students. Earlier this year, I gave a quiz with written-out questions, rather than a blank map. For whatever reason, this really threw my students for a loop. They did TERRIBLY on material I was pretty sure they knew reasonably well. It was clearly the format that was messing them up.

It struck me that reading about countries, geographic features, etc.. in context was pretty challenging to these guys, so I decided to give them more of this sort of quiz, to help them develop those skills. Because - and let's be frank here - how many times in life is somebody going to walk up to them on the street and ask them to identify Wyoming on a blank map?

A couple of the questions I had asked on the "word-problem" quiz had been linked together into a little story. A couple of usually-not-terribly-engaged students mentioned that they liked that narrative, so for the next quiz, I wrote a story about a giant donut monster eating Burlington, Vermont. That went over pretty well (and the grades were a little higher than on the previous quiz), so, a month or so later, I gave them a quiz about Europe being invaded by Radioactive Space Hamsters.

This also went over pretty well (with another small improvement in grades), but there was a little bit of complaining about the dorkiness of my themes. I told my guys not to be too critical, or the next time there would be sparkly vampires. This was greeted with so much horror that I felt obligated to write the following quiz.

(See how you do on it.)

I thought I'd share a student's New England mapping quiz.

With thanks and appreciation to Lee LeFever and Eric Langhorst, here is this year's crop of "Common Craft" movies that my 7th graders made about Ancient Rome:

As always, your comments are welcomed.

I keep a classroom wish list on Amazon. I started it a few Christmases ago, when I received one coffee mug too many, filled with Hershey's Kisses. The idea is that if parents or students feel the need to give me something, they have a list of things that we could really use in my classroom - everything from books to batteries to plastic spoons. I also include the link to this wish list in the letter my colleagues and I send to parents at the beginning of the year, when we send out a request of classroom supplies. One of the items on this year's list was a reprinted edition of the 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalog. I've done a lesson on this catalog for several years, but I've always wanted enough copies for my students to be able to play around with it. So, I made a note on my wish list, that it would be nice if, over the next several years, I could gradually build up a classroom set of these catalogs. On the second week of school, I found a giant cardboard carton outside my classroom door. When I opened it, I found that the parents of one of my students had actually bought us fifteen copies of the catalog. Which left me in the position of having to figure out what to do with them. (Did I mention that the mother is on the School Board?)

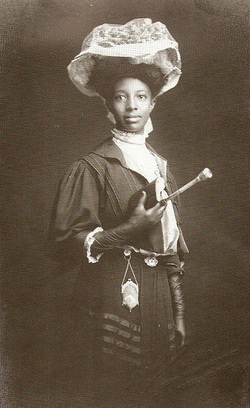

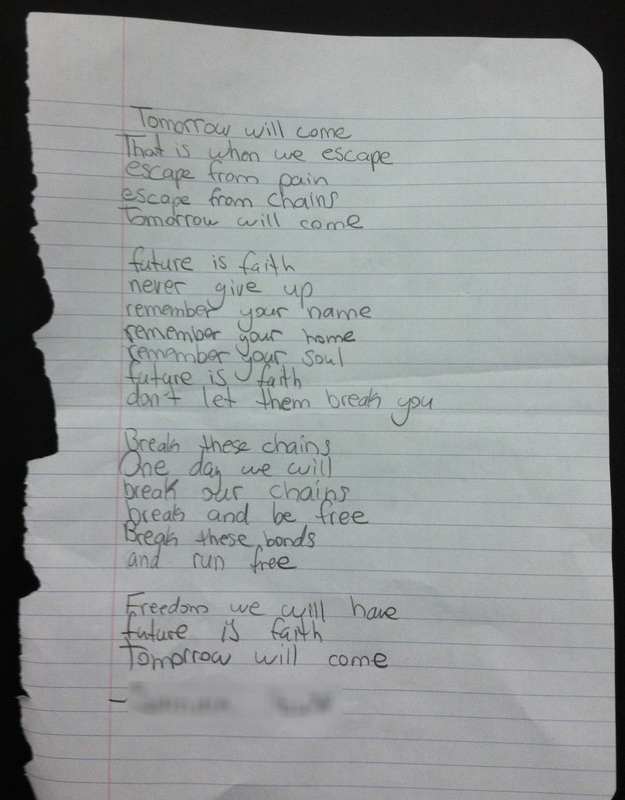

Each year, I show the mini-series Roots to my 8th grade classes. Yesterday, we finished Episode #2, which concludes with a very powerful scene, where the African-born slave, Kunta Kinte is brutally beaten until he renounces his African name and acknowledges his slave name, Toby.

At the end of the day yesterday, one of my students walked into my room and extremely casually dropped this poem on my desk.

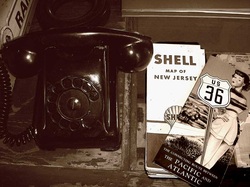

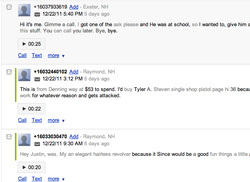

I've had my 8th graders leave voicemail messages on GoogleVoice three times this year. As with all new projects, it took several tries to trouble-shoot the problems that came up. Here is what I learned in the process:

Problem - Students didn't bother to call and leave a message.

Solution - I shared the recordings I received with the rest of the class and had them try to figure out who each message was from the weird, extremely faulty transcriptions of each message. Surprisingly, this made calling in seem fun enough to get most of my guys involved the next time around.

Also, I started a new policy of making up work. Since it was pointless to have students call in after I'd already made a movie using voicemail messages, in order to make up the missing work, they had to complete a textbook assignment for me that was WAY more work than making a fifteen-second phone call.

Problem - "No, Mr. Fladd. I DID call you. If you didn't get the message, it's not my problem!"

Solution - It turns out that several of the students who I was ABSOLUTELY CERTAIN were jerking me around actually did try to call and leave a message. The problem was one of inter-generational communication.

As it turns out, many of my 8th graders have never had to make a long-distance phone call. They don't generally talk to or text anyone outside of our state. If they do, it's generally a grandparent, in which case, they just hit "reply" on their cellphone history. Several of my guys had no idea what an area code is. They have always assumed that the digits in parentheses in a phone number were like the "http://" in a web address - discretionary stuff that only adults care about. A good number of my students did call my number, but not in the right area code.

(When I signed up for a GoogleVoice account, there weren't any New Hampshire telephone numbers available, so I took one in the Detroit area. Somewhere in New Hampshire, there is a confused - and increasingly irritated - customer who is getting a lot of nonsensical calls from 13 year-olds.)

Explaining this and demonstrating it with a borrowed cellphone cleared it up.

Mostly.

Problem - "I tried to call, but it wouldn't let me!"

Solution - Cellphone calling plans work on the concept of minutes, rather than distance and land-lines are generally the way old people like parents communicate, so some of my students didn't know that you have to dial "1" before the actual phone number, on your home phone, if it is out-of-state. Also, a couple of students had tried calling from the telephones in school classrooms, which won't allow long-distance calls.

I addressed this by explaining the problem, then having all my students add a "1" in front of the telephone number they had written down in their notes and planners.

They all felt that the concept of long-distance was pretty stupid, and I find that I don't particularly disagree with them.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed